Tar Fork – Breckinridge County, Kentucky

by Francis W. Keenan – Brockport, New York

A tar like substance oozing from the ground and forming pools was the likely reason a community in Breckinridge County, Kentucky, was named Tar Fork1. Some have thought that the name was related to a fork in the road at this place. And perhaps the proximity of the area to a stream named Tar Creek in the bottom lands just to the west had something to do with the naming of the site. The stream is a tributary or fork off Clover Creek and the latter empties into the Ohio River at Cloverport, Kentucky. From the head waters near Tar Fork and along the way to Clover Creek, Tar Creek passes Tar Springs which was a rather well known spa during the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century. The water from the tar springs under the nearby cliffs was believed to have healing properties and a large hotel on the site was visited by people from many states. The region is part of a karst area known for its sink holes, fissures, caves, springs, cliffs, and underground streams.The fork in the road at Tar Fork had one spur going to the southeast and this was the continuation of the Mattingly to Rock Lick Road or what became County Route 629. The other spur which forked to the southwest was dubbed the Tar Fork-Easton Road. The big road, Rte. 629, that passes through Tar Fork was earlier known as the Cloverport to Bowling Green Road which was built by the State of Kentucky in 1820. There was a church, school, general stores, a Post Office, a saw mill and a blacksmith business in Tar Fork.

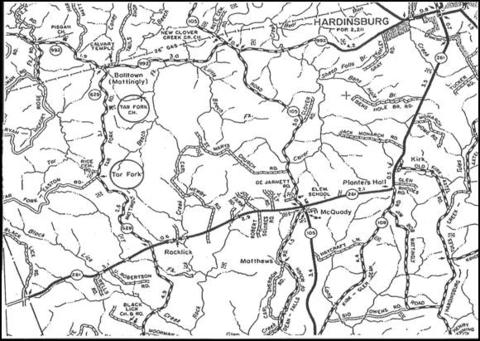

Note: The map was provided by the Ancestral Trails Historical Society, Elizabethtown, Kentucky.

Whether the settlement of Tar Fork was so named because of the pools of dark and tar like water in the region, or because the main road forked there, or because of the proximity to Tar Creek in the bottom lands to the west was unknown. Because the tar substance was prominent in the area, the word 'Tar' in the name was logical. However, the word 'Fork' in the title seemed more appropriately suited to the fact of the road structure in the community and not to the geography of the nearby Tar Creek which forked from Clover Creek as that fork was eight miles distant to the north. And, the bridge near Tar Springs on Tar Creek was often called the 'Tarfork' bridge. However, it was some five miles from the community of Tar Fork.There was another reason posited for the naming of the community as Tar Fork. Historical naming practices in this region favored the use of creek and stream names. The waterways were mostly named by surveyors who surveyed land claims before many people inhabited the area in Breckinridge County. Clover Creek, for example, was named for the abundance of wild clover that grew along its course. The Tar Creek fork of Clover Creek was named for the tar like color of the water and the oil/water pools found near to it. There were maps which indicated that the stream in the upper reaches was named Tar Creek and the lower portion was Tar Fork. For example, in 1909, a petition was filed asking that the bridge on Tar Fork creek near Tar Springs be repaired as the Cloverport merchants were losing thousands of dollars.2 Farmers were diverted to Hardinsburg or Hawesville because of damage to the bridge from a flood.

Tar Fork, the community, and Tar Creek the stream were one and the same for a while. The first Post Office there was officially named the Tar Creek Post Office. It later became the Tar Fork Post Office. The two names, Tar Fork and sometimes Tarfork became synonymous with Tar Creek. Many who used this Post Office lived in the bottom lands on both sides of Tar Creek. It was no wonder, then, that the first post office for the town was called Tar Creek Post Office.The Tar Fork settlement has passed into history as a registered township. The Post Office there closed July 15, 1935, after 59 years of service. Settlers had lived along this ridge top community as early as 1792 when Kentucky was admitted to statehood. Even prior to statehood, land barons had come into western Kentucky to secure land for they anticipated the migration to come as Easterners traveled in search of land from which to obtain a living. The westward movement of the early 1800s saw increases in population throughout western Kentucky. The largest influx of people into Breckinridge County occurred about 1880. The industrial cities to the north attracted many people because of the availability of jobs in the factories. Of those who came to Tar Fork, many were tenant farmers, share croppers, hired hands. Others bought deeded land. Most of these people eventually continued the westward migration and journeyed to Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. Some joined wagon trains headed for the Oregon Territory. Those who stayed along Tar Creek were mostly tobacco farmers who engaged in general farming.

These were tumultuous times. In 1886, Grover Cleveland was President and John Knott of Marion County was the Governor of Kentucky. On May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, there was a major riot. A rally in support of striking workers turned ugly. A bomb was thrown at police and eight officers were killed and an unknown number of bystanders. Eight anarchists were tried and four were executed. Another committed suicide while in prison. The polarized attitudes of business and big labor unions were the causes.3 Also in 1886, the American Federation of Labor was founded in Columbus, Ohio. In 1889, the Oklahoma land rush occurred on April 22nd. There probably were land seekers in that race who had previously lived in Breckinridge County, Kentucky. At the end of this decade, the massacre at Wounded Knee occurred. Thankfully, the contentious air found elsewhere was not so apparent in Tar Fork. In fact, the newspaper, the Breckinridge News, was not yet in business in 1886. News, therefore, likely was by word of mouth for the most part on this ridge and in the area known as Tar Fork.Tar Fork was near to many other small communities and was often referred to, sometimes erroneously, as: Tarfork, Tar Creek, Mattingly (aka, Balltown), Tar Springs, Liberty Hall, and Hickory Lick. None of these communities had distinguishable boundaries and those living on the edges of one could have been listed as citizens of another of these nearby communities, even sometimes Cloverport or Hardinsburg. Tar Fork was south of Mattingly exactly three miles. It was west of McQuady (aka, Planters Hall), north of the old Hardinsburg to Hartford Road, and east of Cabot, Kentucky. It was not far from the eastern Hancock County boundary line. Secondary roads in those days were merely wagon paths also used by horse back riders, buggies and buckboards as the automobile was not yet part of the landscape.

Perhaps the official beginning for Tar Fork was when the first Post Office was assigned to the area. In the records this Post Office was first listed as Tar Creek and the first Postmaster was Thomas H. Bates, appointed 23 July 1874, and his assistant was Thomas O. Ryan.4 W. L. Ball was appointed as Postmaster for Tarfork on 21 May 1886, and Thomas H. Bates again on 24 Aug. 1887.5 Bates and Ryan had lived there long before the Post Office came into existence. Tar Fork was thriving before the Civil War began.Thomas H. Bates, the first Postmaster, was born November 22, 1839; he was a son of John D. and Theodocia Compton Bates. John Bates had purchased land in Tar Fork in 1851. His father, Sam, came from Lexington and moved to a Cloverport farm where he was buried. Son Thomas moved from the farm in Cloverport to Tar Fork. He later became a member of Co. K, 3rd Regimental Kentucky Cavalry, USA, and was at the battle of Shiloh and the engagements during Sherman's march to the sea. Tom married Annie L. McCarty. Benjamin H. Bates came to Tar Fork in 1855 and Jeremiah Todd Bates also came there in 1867. They were variously listed in census data as “tobacconists” which meant that they farmed tobacco crops. Others were dubbed as lumbermen, farmers, sawmill operators, and mill workers. Bates lived in Tar Fork near the Sam Rice and Chancellor homes. In 1900, Thomas Bates was also the official enumerator in his district for the U.S. Census survey.7

It was not until 1907 that a mail route was established for the Tar Fork area. “Wash” Robbins won the contract to carry the mail from Tar Fork via Mattingly and to Cloverport beginning March 15th, 1907. The mail route was named Route # 1 and served approximately 1,000 people, mostly farmers, between Cloverport and Hardinsburg with Mattingly and Tar Fork included along the way. This home delivery route assured that the citizens no longer needed to travel to Cloverport or Hardinsburg to receive postal mail. Dr. William Howard of Mattingly and L. V. Chapin of near Cloverport were primarily responsible for organizing the petition for this mail route which eventually won government approval.8

The first Ryan known to have entered Breckinridge County was Thomas Ryan, Sr. He was born about 1750 in Ireland and died in 1841 in Breckinridge County. He came to Breckinridge County from Nelson County, Kentucky, in 1810 when he was about 50 years of age. His home was just east about a mile from what became the dam for the Corp of Engineers Rough River Lake. The site of his home was covered by water after the dam was built. His son, Morris Ryan, was born June 24, 1794, in Maryland. Morris was a long time resident of Tar Fork. During the summer of 1856, Morris became ill. He developed pneumonia and died on August 6, 1856 at his Tar Fork home. He had been attended by Dr. W. D. Owen, a local physician. He was buried in the Tar Fork (or Ryan) Cemetery on the old Ryan property in Tar Fork just a few hundred feet from County Route 629. Morris had married Cintha (Cynthia) Hall. The Morris Ryan home, which no longer exists, was built in the 1830s and was about 50 yards from the Ryan Cemetery. Their son, Thomas O. Ryan, was one of the early Postmasters for Tar Fork. Thomas Owen Ryan was born September 3, 1830, and died May 20, 1915. He was buried at the St. Romuald Cemetery in Hardinsburg, Kentucky. He had married Elizabeth Priscilla Beavin, the daughter of Samuel Beavin and Elizabeth Mattingly.9When Tom Bates was Postmaster, some of the local citizenry were: J. Beavin, saw and grist mill operator; O. W. Hendrickson, carpenter; W. Howard, physician, J. B. Rice, general store operator, Thomas O. Ryan, gunsmith and surveyor; Powell Tabeling, carpenter; Levi Voyles, constable; and Hardy Walker, justice of the peace.10

In the 1840s, the cannel coal and oil business was underway and the mines were just one ridge west of Tar Fork in Hancock County, Kentucky. Cannel coal from the Bennettsville mine there was eventually reduced to oil and wagons hauled barrels to Cloverport for transport down the Ohio River, to the Mississippi River, and south to New Orleans. This route was necessary because the Falls of the Ohio and shallow water at Louisville precluded shipment to the east and up the Ohio River. From New Orleans, the coal and oil, a rich cargo, was transferred onto ocean-going vessels headed to England. There, some of the oil was used in the lamps of Queen Victoria. As a result, the mines became known as the Victoria Mines and there exists today a road in that vicinity called Victoria Crossroads. The Keg Branch Road off County Route 992 also went to Bennettsville in Hancock County, where the mines were located. It was one of the major routes for transporting the coal and oil to Cloverport. There were miners there from as far as Ireland. The railroad to the mines was built in 1855.11 Bennettsville, no longer in existence, was only a scant few miles from Tar Fork as the crow flies and, in this instance, as the old wagon roads went. When technology was developed to process kerosene from crude oil, the more expensive cannel coal became a fuel dinosaur. Kerosene was called “coal oil” by locals and continues by that name even today.Another reason for the increase in population at Tar Fork was the availability of deciduous hardwoods. The hillsides for miles around were simply filled with trees of all sorts. The geography, therefore, led to the development of saw mills for the influx of people led to the need for processed wood for homes, barns, pens, sheds, fences and the like. Wood was also a staple crop for the Cincinnati Cooperage Company which came to the area to make barrel staves for the coal and oil produced from the Victoria Mines. Barrels were also an important part of the whisky industry in Kentucky, especially at nearby Owensboro. And too, there were a few moonshiners along the upper reaches of Tar Creek and there in the woods around Tar Fork and they also used wooden barrels to store the mash for their “white lightning.”

William Lynch, an executive with the Cincinnati Cooperage Company, moved his family from Mattingly to live on company property in Tar Fork. He had previously, in November of 1905, purchased 400 acres from the Cincinnati Cooperage Company for $3,000. The land was considered valuable because of the timber upon it and several dwellings.12 The house on the old James Patrick Keenan property was destroyed in 2010, over one hundred years after it had been built from yellow poplar planks..

Jesse Marlowe of Patesville was at work for L. S. Powers who represented the St. Louis Stave Lumber Company, which also needed processed wood. The sawmill was a busy place. Jesse was also employed by the Cincinnati Cooperage Company (CCC).13 Jesse was living in Tar Fork at the time of his CCC employ.

As the railroads began to expand westward and were building right of ways in Breckinridge County prior to the Civil War and after, the hardwoods of the Tar Fork area, and elsewhere, were harvested to become railroad ties. The railroads, thereby, became another reason for the increase of population in the Tar Fork community and the business of railroad ties continued for decades. As late as 1900, Gus Gibson, working extensively in the timber business, had cut enough timber to make 4,000 railroad ties.14

In 1903, J.D. Seaton of Tar Fork and Sam Cooper of Hawesville had 10,000 ties stored on the eastern shore of Clover Creek at the mouth of the stream. The ties were set for shipping down the Ohio River to the Moss Tie Company of Evansville, Indiana. The ties were made in the woods south of Tar Fork.15 The tie business was booming and was a benefit to residents of Tar Fork who were employed in the cutting and transport of timber. It was also a dangerous occupation. For example: 'Patrick Henry “Pad” Keenan was badly injured, though not seriously, and had a narrow escape from death when at the sawmill a log rolled upon him. He was taken in a buggy by Tom Rogers to the home of Mr. Rogers and there revived and finally removed to his home in Tar Fork.'16The Evansville Tie Company had a large plant in Evansville for treating railroad ties and white oak timber was made serviceable for ties They wanted ties and timber tracts near railroads or rivers for easier access to transportation. They advertised in the Breckinridge News newspaper.17 Their ads asked that they be addressed at Evansville, Indiana, or F. E. Matheny at Stephensport, Kentucky. Many a farmer during the great depression and after a long day in the field would fell a tree and with a broad ax hue out a railroad tie for sale to the railroad companies for fifty cents a tie.

Before the dams were placed upon the Ohio River, floods were common along the Clover and Tar Creeks. During the 1884 Ohio River flood, the water was seven feet deep in the Tar Fork Bridge floor.18 This bridge was near to and just north of the Tar Springs Hotel and was the site of the Tar Fork covered bridge. The bridge spanned the Tar Creek fork of Clover Creek. The covered bridge no longer exists there but a bridge yet spans Tar Creek in the same location.The general store in Tar Fork was first operated by Thomas Owen Ryan and Charles Tabeling. Charles had married Thomas Ryan's sister, Ida Susan Ryan.19 Later, there was also another general store in Tar Fork; this one was operated for a time by Corbett Keenan (1890-1975). Also, L. C. Taul had a general merchandise store which he sold in 1905 to Norvin and T. H. Chancellor. The Ryan store was located across the road from the Chancellor store.20 The school house in Tar Fork was dubbed the Thomas Ryan School. It was located on the Tar Fork-Easton Road and not far from the fork. Miss Mollie Goff was appointed as the teacher for that school effective September 26, 1883.

'In 1884, Mrs. Jennie Goff, wife of Charles Goff, died at age 32 years at her home on the Bowling Green Road in Tar Fork. Jennie was engaged in tacking down a carpet fronting the fireplace. She accidentally caught her dress on fire when she backed onto the fireplace hearth. She ran outside to the water trough and found it frozen. In pain, on fire and in a panic, she ran to the well to throw herself into it and was halted by her aged mother who dashed Jennie, now fully engulfed in flames, with water from the well. Jennie died of her burns.21The Rev. Charles Goff came to Tar Fork about 1850. He was minister at the Campbellite Christian Church in 1909. This church was 1.9 miles north of Tar Fork. Rev. Goff also serviced the Cave Spring Baptist Church in Tar Fork. During the Civil War, Charles had escaped capture by Rebel forces by swimming across the ice filled Kentucky River. One of his descendants, Charles L. Goff, III, born in 1930, continues to live there.22 He married Emma Robertson. The Goff farm had previously been deeded to James Chancellor. To the south of the Goff farm was one owned by Washington Robbins, the mail carrier and farmer.

The Goff family had a long history in Tar Fork. Charles Louis Goff was born in 1844 in Cannelton, Perry County, Indiana. He was a son of John Stogsdill Goff and Nancy Elizabeth Steele. Charles married Eliza Jane “Jennie” Bates. When she died, he married Mary Jane “Molly” Hawkins. Charles was buried between his two wives in the Rice Cemetery in Tar Fork. Charles and Mary had a son, Charles Louis Goff, Jr. ((1900-1961). Charles Jr. was a county agricultural agent. He married Derl Elizabeth Cress. Charles, the ag agent, was well respected throughout the state. He had sponsored many 4-H clubs in Kentucky. He was known to have taken a carload of youngsters to the state 4-H convention in Lexington in his new Hudson automobile and they stayed in Bradley Hall on the campus of the University of Kentucky and had a great time.Some of the residents of Tar Fork that were listed in the 1860 Federal Census were: William Robards, Robert Montgomery, John Freeman, Lawrence T. Keenan, George and William Mason, George Mullen, William Furrow, Thomas McMasters, James Newton, Edward Barbee and Woodson Boling. The Post Office listed for them was Hardinsburg, Kentucky, but they lived near Tar Fork.23

By 1870, the census for the Tar Fork area listed the Post Office as Cloverport, Kentucky. Some residents were: Ben Bates, Samuel Muffet, Lawrence T. Keenan, James Chancellor, Henry Seaton, Thompson Ludwick, Thomas Ryan, and James Barbee, among others.24By 1880, the community had grown significantly as the following list of residents for the Tar Fork area from the census of that year will testify. Some representative names were: Benjamin Bates, Patrick Sherron, Charles L. Goff, Francis Riley, J. L. Barbee, H. Quisenberry, James Beavin, Thomas Ryan, Jackson Newby, Lewis Miller, Owen Seaton, L. T. Keenan, Todd Bates, John Riley, William Jackson, Thomas Pate, John Hinton, Julius B. Jackson, Leland Prior, Patrick H. Keenan, Richard Hawkins, Robert Mingus, Ben Dean, Sam Taul, James Rice, Sam Rice, Owen Rice, Thomas Beavin, and George Askins.25

A few from Tar Fork whose names appeared in the 1900 census were: James Dunn, John Harris, George Beatty, William Beatty, a McManaway, John Wells, Thomas Muffett, Thomas Rogers, Francis Weatherford, Thomas Bates, Sam Rice, Mildred Newby, James Chancellor, Sam Bowman, Patrick H. Keenan, Lafayette Taul, Charles Barbee, and B. Wells.26 (The 1890 Federal Census was not available for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.)By 1910, the census for Tar Fork displayed some of the same surnames, listed above, as well as some new ones which were: Naomi McQuady, Ed Hook, Charles Tabeling, Noah Sanders, Horace Fuqua, Dorsey Bratcher, John Easton, Asher Newby, William Ryan and Thomas Chancellor. Still there were: Thomas Ryan, Owen Rice, John Wells, Charles Goff, James Dunn, William Beatty, among others. Some of the others were: James Marlowe, Robert Weedman, Thomas Bates, James P. Keenan, Elijah Board, Julius Jackson, Alfred Hawkins, Moses Baum, Sam Bates, William Taul, James J. Keenan, and Gideon Burdette.27 (The foregoing lists of names from census data were not intended to be inclusive and were only a representative sampling of the names of residents of Tar Fork during the years reported.)

The Cave Spring Baptist Church in Tar Fork was founded in 1886 (photograph from Frances Goff Miller). The Sunday School Superintendent was W. H. Bates of Tar Fork. The church was not listed among the Breckinridge County churches until 1900, A cemetery was established near to it and was renamed the Rice Cemetery.28 The cemetery was indexed in October of 2000 by Edward Hook. Numerous instances of each of the following surnames were listed including: Bates, Chancellor, Elmore, Fuqua, Goff, Heth, Hook, Lyons, Mason, Murphy, Newby, Rice, Sanders, and Smith.29 The pastorate was difficult to fill and many preachers came to Tar Fork to provide services for the Cave Spring Baptist Church. Poor attendance numbers often led to the postponement of services for an indefinite time. The Rev. Joel Talbert Keenan preached there on Wednesday, July 11, 1906.30 Rev. Keenan, a Methodist Episcopal minister of the Gospel, was a grandson of Patrick Keenan (1776-1832), a native of Ireland who settled near Falls of Rough in 1918. Rev. Keenan's family had traditionally lived near Tar Fork. A chapel called the Keenan Chapel was built just west of Tar Fork at Hickory Lick.Many small churches popped up here and there in Breckinridge County and most soon failed as populations shifted dramatically and the churches lost the financial support needed to exist. Some members of failed churches were assimilated into other area churches one of which was the Pisgah Baptist Church just west of Mattingly on County Route 992, just 4.4 miles from Tar Fork. The Pisgah Church was the oldest Baptist Church in the area and periodic services continue there. There are yet occasional dunking baptisms performed in Tar Creek by local churches either at the Keenan/Ferguson ford or at the Newman water hole both of which lay along the Lamar Ryan Road.

The Campbellite Christian Church between Mattingly and Tar Fork on County Route 692 has a number of graves of Civil War soldiers in the cemetery aside the old church. They were: B. H. Bates, Pvt., Co. A Infantry, Green River Battalion, USA; Thomas H. Bates, Co. K, 3rd Kentucky Cavalry, USA; Hiram Blair, Co. L, 3rd Kentucky Cavalry, USA; Charles L. Goff, Cpl., Co. D, 12th Kentucky Cavalry, USA, and a messenger boy at age 15; James Monroe Marlow, Sr., Pvt., Co. F, 16th Kentucky Infantry, USA; Samuel Muffett, Sgt., Co. K, 3rd Kentucky Cavalry, USA. The land for this church and cemetery was donated by John and Susan Hinton and E. B. and Bettie Barber.31Another cemetery in the Tar Fork community was the Keenan family cemetery. It was established on the farm of Lawrence Thomas Keenan, born in 1829. He purchased the farm in 1850. His son, James J. Keenan, farmer and a Clerk for the County Court, inherited the farm and later one of James' sons, John Russell Keenan, Sr., also continued farming there. The farm did not remain in the Keenan family and the cemetery fell into disrepair.32 Other surnames in this cemetery with tombstones included Furrow (2) and Taul (3). Mr. Larry Keenan, a son of John Russell Keenan, Sr., continues to live near Tar Fork on Rte. 629 at a marker there named Keenan Mountain.

At one time, there was a music school in Tar Fork for the Breckinridge News reported that Professor John Burnette closed his music school at L.C. Taul's and began teaching at “Nobe” Pate's home place.33Recreation was another matter. Baseball was played at Mattingly, Kentucky, just three miles from Tar Fork, and the team there likely led to the community receiving the nickname of “Balltown” in honor of that pastime. The ball field was on the southeast corner of the intersection of County Routes 992 and 629. The land was most recently owned by the Herman Mattingly family. Many young men from Tar Fork played baseball there. The ball field like the Town of Tar Fork has faded into history except in the memories of some aged former and local citizens.

A quirky pastime came to light after a night in the dark. Thomas and Patrick Keenan, Stylie Keenan, and Homer Taul went possum hunting and came in with sleepy eyes and greasy mouths.34 YIKES! What were they doing out there in the woods at night? Others took to seining the creek for fish and gigging frogs. But, as an ancient philosopher said, the boys kill the frogs in jest but they die in earnest!Life was difficult in these Kentucky back woods communities. There was no electricity until the mid-1950s for many of them. Coal oil lanterns were the norm. Also, wells, cisterns and springs served the need for water. There was no television. What radios were in the homes were powered by batteries and could not reach many stations and were filled with static. One family reported trying to listen to the Joe Louis vs. Jersey Joe Walcott heavyweight championship boxing match on December 5th, 1947, only to have the radio fail as the batteries lost their energy. The outhouse was the standard procedure for excretory requirements and lime was used in them as well as in the cisterns and wells for hygienic purposes. Cooking was done on wood burning stoves and heating was done by the same method in most homes until heating oil became available. Washing clothes was done in large iron kettles and on scrub boards. The soap was made from hog fat and lye. Most of the food supply, vegetables and meat, was raised upon the farm. Telephones became available well after WW II. The result of this kind of primitive life led to a closeness and firmness of purpose that spurred people to succeed despite the hardships. Doing the “chores” began before first light as wood was split for the stove so that biscuits and coffee, bacon and eggs could be made for breakfast. The cows were milked by hand and the chickens fed. The hogs were slopped and then, after breakfast, it was to the fields to work in tobacco, corn, hay, beans, and the like. The women separated the cream from the milk and sold it along with the chicken eggs in order to have money to buy coffee, salt, sugar and other necessary staples which could not be produced upon the farm. They also quilted and sold the blankets. Some made work dresses and bonnets from feed sacks to save money during the great depression era.

Farm implements were powered by horses and mules. These farmers were at the mercy of nature and long drought periods could substantively affect the market price of their staple crop which was tobacco. And, there was always the issue of a farm accident which could cripple or kill. The felling of trees was dangerous and wood was always important to many facets of farm life including the building of fences. A horse or mule could kick and maim a farmer. There were rattlesnakes in the woods, copperheads in the fields and cottonmouths in the creek. Life was dangerous. In an odd accident, while tombstones were being loaded onto three wagons at the J. E. Keith and Sons Monument Works, a team of horses became frightened and bolted. A 71 year old man from Tar Fork was struck in the head by a falling stone and seriously injured and two of the wagons broke. He was taken to his home by Mr. Keith and he survived the injury.35 It would have been a tragic story if the poor man had needed one of the tombstones as a result of his work with them.While these were hard times, the roaring twenties just ahead was a palliative for farm markets and the mechanized era of farming was beginning. The introduction of powered farm machinery and implements meant that Tar Fork's hired hands and share croppers were no longer in high demand. They had been necessary during the manual period to plant, lay bye, harvest and move crops, especially tobacco, to market or storage. Most of them owned no land and now they removed to other locales in search of employment.

After the 1920s came the financially devastating great depression. In the middle of the 1930s, and nearing the end of this especially dramatic period in the history of the United States, the Cave Spring Baptist Church and the U. S. Post Office at Tar Fork both failed. Their demise was related to the shifting of populations and the decrease in the number of inhabitants in the Tar Fork area. There was literally a stampede of people to the factories in Louisville, Detroit, and other northern manufacturing centers. Many farms went into default and were repossessed by the banks. Those who could not meet financial obligations lost their life's work and many moved to other venues. The survivors in Tar Fork were able to raise enough food and sell just enough of their staple crops and livestock to maintain their farms and residences. Many other small communities in Breckinridge County slid into the abyss of history and no longer existed as thriving towns. Some of these were: Lost Run, Planters Hall, Prince of Wales, Rock Lick, Rough Creek, Franks, Haycraft, Ruff, and Matthews, to name a few other post offices that disappeared.Much of the land in and around Tar Fork has been managed in recent times for the hunting of deer and wild turkeys. Some of the land has been leased for the same purpose. As the allotments for tobacco changed, the farming of it there was diminished.

Despite the loss of this community, Tar Fork, the people who lived there provided lasting memories and essential values in their lives and those of their descendants. Family reunions were often held each year near Tar Fork 36, especially by the Bates and Jackson families. Stories about the region and its people and life's struggles were relayed to younger generations at these meetings insuring that Tar Fork, its people and its legacies, managing tobacco crops, farming, mining, and the timber industries that thrived there would not be forgotten.

1 This essay about Tar Fork was written to honor the memory of my mother, Mary Marcella Keenan. Her maiden surname was Keenan and she married Wilbur Eaton Keenan. She was born in Tar Fork in 1908 and died in 2002, in Danville, Illinois.

2 Hartford Herald, March 31, 1909, p.2.

3 Wikipedia, Haymarket Affair

4 National Archives and Records Administration, Microfilm Publication M481, Roll #44, Post Office Superintendents, Washington, D.C.

5 Ibid.; it was noted that the official record named Thomas Bales as the first postmaster. However, no one named Bales ever lived in or near Tar Fork. The Bales entry was an obvious misprint or misread of the Bates surname.

7 Breckinridge News, May 25, 1910, p. 1.

8 Breckinridge News, September 16, 1903.

9 The Ryan information was taken from: Perry T. Ryan, The Ryan Family of Breckinridge County, Kentucky. Utica, Ky.: McDowell Publications, 1983.

10 Gary Kempf of Ancestral Trails in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, provided this information from his files.

11 The Breckinridge News, Wednesday, May 17, 1905, p. 3.

12 The house occupied by Lynch was later sold to Gideon Burdette and son. The Burdettes sold the house and land to James P. Keenan, maternal grandfather of the writer, in 1918. The farm on Tar Creek at the terminus of the Lamar Ryan Rd. remained in the Keenan family owned by a grandson of James Keenan, also named James Keenan.

13 Breckinridge News, February 14, 1906, p. 1.

14 Breckinridge News, February 21, 1900, p. 5.

15 Breckinridge News, October 21, 1903, p. 1.

16 Breckinridge News, October 4, 1905, p. 1.

17 Breckinridge News, Wednesday, July 24, 1907, p. 5.

18 Breckinridge News, January 23, 1907, p. 2.

19 Electronic mail message from Perry T. Ryan to Francis Keenan, August 16, 2010.

20 Guida Goodman Snavely. Breckinridge County Kentucky History. Vine Grove, Kentucky: Ancestral Trails Historical Society, Publishers, 2005, p. 97.

21 Breckinridge News, February 20, 1884.

22 Charles L. Goff, III, graciously granted an interview to the author and, at that time, provided considerable historical information concerning Tar Fork.

23 1860 Federal Census for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

24 1870 Federal Census for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

25 1880 Federal Census for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

26 1900 Federal Census for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

27 1910 Federal Census for Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

28 The Cave Spring Baptist Church at Tar Fork was dismantled in 1935 and removed to what became New Clover Creek Baptist Church which is extant today on Rte 105 in Breckinridge County, Kentucky, just a few hundred feet from the intersection with Rte 992. This information was supplied by Perry Ryan from the Minute Book of the Cave Spring Baptist Church. William Taul, deceased, indicated that the Cave Spring Church in Tar Fork was moved by horse drawn wagons.

29 There were sixty graves listed with birth and death dates. These can be accessed at USGENWEBARCHIVES on the internet, Breckinridge County, Cemeteries.

30 Breckinridge News, July 11, 1906, p. 7.

31 Snavely, Ibid.

32 In 2001, Francis Keenan and Wayne Meador cleaned the Keenan family cemetery and repaired broken stones. They raised a few grave markers from under the ground.

33 Breckinridge News, July 19, 1905, p. 4.

34 Breckinridge News, January 5, 1910, p. 5.

35 Breckinridge News, August 19, 1903, p. 5.

36 It was at a Keenan family reunion in 1929 that Mary M. Keenan of Tar Fork met Wilbur Keenan of Illinois whom she married in 1931. The family of Wilbur “Dick” Keenan had migrated from Breckinridge County to Illinois early in the 20th century.